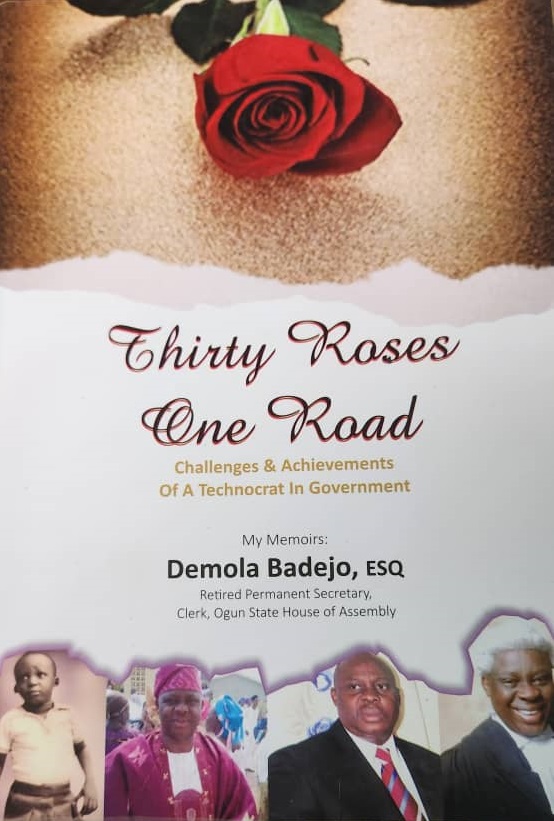

A review of Thirty Roses One Road: Challenges and Achievements of a Technocrat in Government; Memoirs of Demola Badejo, retired Permanent Secretary/Clerk of the House of Assembly, Government of Ogun State, Nigeria, delivered on 20 January 2022 at the Valleyview Hall, Abeokuta

Introduction

It was the publication, early in 2001, of the compendium, Ogun at 25 that first brought the name of Demola Badejo to the attention of many of us on the team that was then crystallizing around the quest of Otunba Gbenga Daniel to emerge as Governor of Ogun State at the 2003 elections.

As was to be expected of any serious political quest, opponent research was a key aspect of our remit. And since it was our purpose to displace the incumbent, the activities of the government of the day was naturally our special focus.

Added to this was the fact that we were at the time also preparing for our own commemorative event to celebrate the Silver Jubilee of the creation of our dear State in February 2001, under the auspices of the Gateway Front, the special purpose vehicle that was the precursor of the Otunba Gbenga Daniel Campaign Organisation (OGDCO). It was in this context that the above-referred publication came to our possession through some channels.

The first thing that struck us was the high level of professionalism displayed in the publication both in terms of its editorial content and the savviness of its presentation. As we sought to find out the brain behind it, the name of Demola Badejo popped up for the first time in our circle. The name was strange to many of us, but may have been known to a few in their private capacities.

Of course, divers passions and reactions were to trail this discovery. Some argued that only a core loyalist of the then Governor Olusegun Osoba could have pulled off such a celebratory publication with such panache and elan. I think that it was from this that the appellation, “Osoba Editor”, coined by Niran Malaolu, my predecessor at the Information Ministry, emerged.

There were also some amongst us who argued that the quality of the publication spoke more to competence than to partisanship. It was a little detail that Otunba Daniel obviously filed away for future use. Niran’s alias for the author was to stick. And this was to be the subscript to the testy exchange between the author and Governor Daniel in the heat of the House of Assembly crisis, as narrated in the prologue to this volume.

Demola had invited me sometime ago to contribute to this book as a witness in part to his interesting life story, especially the aspects of it that had to do with his civil service career. I cannot recall if the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic was just a convenient excuse for my inability to submit a contribution as requested. However, it seems that being asked to review this book is my punishment for not meeting the earlier deadline. It is indeed a punishment that I so gladly accept even as I put the author on notice that what he gets in this review is what he gets!

Review

In the early part of his life, Demola was nearly knocked out of this world by a vehicle as he played on a road that he, in a toddler’s innocence, had assumed to be part of his maternal grandfather’s sprawling estate. He survived. In the twilight of his civil service career, Demola was also to be nearly knocked out in a vicious power struggle that he, as a civil servant, had no hand in making. The tussle was between two arms of government – the Executive and the Legislature. Again, he survived.

From the polar extremes of these two life-threatening incidents he has now crafted an enchanting story of courage, duty, fortitude, perseverance and triumph.

Thirty Roses One Road is a book of twelve chapters and two appendices, written in reader-friendly prose by a participant observer in the drama of politics and governance and life in Ogun State. Were this to be an account of the author’s exploits in business, its title also could easily have been flipped around to read “Thirty Roads, One Rose”. This is because as a “gbogbolowo” expert, he has navigated the business journey to an end that does indeed smells like a rose!

The book, expectedly, begins with his childhood stories mostly told by an elder sibling. These stories present an intimately personal narrative that is also a painful reminder of the Nigeria we lost. It was the Nigeria where a child was raised by every adult in the neighbourhood; where a good name counted for a lot more than silver and gold; and where functional public schools were good enough for the children and wards of the high and mighty to be enrolled in alongside the children and wards of the poor and lowly. It is a Nigeria that we must strive to regain.

Tributes from various people Demola encountered in his interesting life journey intersperse the book. The casual reader may feel that these tributes could have been better consolidated under a general chapter. But the way these tributes have been woven into the relevant chapters not only speaks to the author’s standing as a great editor but also enrich the book considerably.

I crave your indulgence to quote one of the eye-witness testimonies from Demola’s childhood friend, Lekan Mako:“Demola was a ladies’ man … not into so many but never lacked at any time.” This is one testimony with which many here may be able to relate. No doubt, the author thoroughly enjoyed his growing up years as well as his schooldays. These prepared him very well for the work life that he was soon to assume. Apparently, he had very few early life fantasies that he felt a need to overcompensate for in his adulthood.

Demola’s accidental interview for entry into the civil service stands as one of the very many instances of divine intervention in the life journey of this easy-going man of deep convictions. His was probably the last set to truly enjoy the fruits of the old Nigeria. And he did build a solid team of friendships that have lasted to this day. Friends such as Sola Adeyemi and Kayode Oyesiku whose paths and his crossed and criss-crossed across several decades.

At work, sycophancy was not the author’s forte. This was to be shown by his disposition to the “Thank You” visit by some of his fellow newly appointed Permanent Secretaries to the Governor. Maybe he had concluded that the biggest “Thank You” for a job given is to do it well. The words of Oyesiku at p.40 are relevant here: “For me, Demola Badejo has demonstrated quintessential qualities in his various positions up to the time he was a Director in the Ministry of Information and to the time he became a Permanent Secretary, which (have) made him very successful”.

The success that Oyesiku alludes to here were greatly helped by the primary building blocks provided by good upbringing, which combined with a trained intellect and a capacity for imagination to assist him in weathering the many storms of his service years. These were to also manifest in the unforced way in which he extracted obedience and support from his subordinates.

Paying tribute to subordinates would seem to be a very unNigerian trait. In our clime, bosses often present themselves as “do it alone” supermen. But not Demola. His glowing commendation for role played by Gbenga Fabuyi and Titi Olusesi in his successes are a hallmark of his nobility of spirit – and surely must be one of the secrets of his success.

So also are his references to the contributions of Messrs Biodun Awere and Kehinde Onasanya in making his administrative yoke easy at the Ministry of Information. As Fabuyi attests at p.74, once you show competence and character as a junior officer, Demola immediately accepts you into his circle of colleagues.

It is perhaps no surprise then that just as he celebrates his subordinates, Demola’s superiors also had no difficulty acknowledging him and singing his praises. The testimonies of his bosses such as Alhaji Fassy Yusuf, Dr. Dele Ogunsiji and Dr. Niran Malaolu amply bear this out.

This book shows the author to be an exemplar of the government information manager as a door that opens both ways – into the inner recesses of the state apparatus and also into the mind of the general public. He was to add a third opening – into the world of the mass media through his union activities amongst his professional colleagues.

Acknowledging mentors is yet another attribute that Demola has in abundance, as copiously captured in his memoirs. Just as several bosses have great difficulty accepting that they stood on the shoulders of others to reach the top, many successful people also have the unfortunate trait of climbing to the zenith of their careers and promptly taking the ladder with them.

Again, not Demola. He celebrates the great Kola Bamgbelu, Femi Olurin, Papa Ogunfowora and several other mentors. Imitation being the compliment that wisdom pays to excellence, he modeled himself after these stars and in the process became a star himself.

Yet, one area in which he admits his frustration is the perennial crisis that dogs his professional union, the Nigeria Union of Journalists. The crisis was there at the inception of his civil service career. And it persists to this day, four decades later. It is indeed a sad commentary on the pioneering role of our dear state in the development of the noble profession of journalism that these challenges continue to resurface with heightened intensity in the cradle of the profession in Nigeria. The gory picture that he paints of the state of the iconic Iwe Irohin House is emblematic of this miasma and is nothing short of heart-rending.

But given his love for the journalism profession the author is not content to just lament. He has also proffered some solutions in this book. He wants the contest between professionalism and unionism to be resolved once and for all. He notes that issues around check-off dues, touting, etc still cry for attention. And he calls for the strengthening of practice rules, setting strict entry level requirements and making adequate provision for continuing professional education.

The author has every reason to want to continue seeing the journalism profession go places. It was journalism, after all, that made him, albeit through the instrumentality of the civil service.

His gripping account of how the Iwe Irohin House project saw the light of day through that 11pm call from the then Military Administrator, Navy Captain Oladeinde Joseph demonstrated the emergence of the enterprising pressman as a power broker. That the remodeled Iwe Irohin House is today a shadow of its former self does not in any way subtract from the substance of the immense influence broker role that Demola Badejo played in bringing the project to life.

But this book also dwells on happier circumstances. As Gboyega Okegbenro attested in his contribution titled, “Demola Badejo… Everything Good in Creation”. Okegbenro confesses that the author helped to change his perception of civil servants as do-nothing time-markers. It is a view that many professionals who have had dealings with the civil service are likely to share.

Today, not many people would remember the arid land that the operations of the State Ministry of Information was in 2003 when the Daniel administration came on board. It is a testimony both to the farsightedness of the then new government and the availability of progressive-minded officers such as Badejo that the Ministry within a few years became a trailblazer in Ogun State’s entry into the Digital Age.

The testimonies of media friends captured in this volume read like a who’s who list of the Nigerian media. From the grand old man of the profession, Aremo Segun Osoba to Alhaji Fassy Yusuf to Alhaji Lai Labode to Sina Ogunbambo to Prince Jacob Akindele, Eddy Aina as well as younger elements such as Dr. Yemisi Bamgbose, Gboyega Okegbenro, Gbenro Adebanjo, Enitan Taiwo and many others – all of who pay glowing tributes to an astute professional who deftly brokered government-press relations.

His description as the “Samurai of modern journalism” by no less a person than Bamgbose, a frontline labour leader and czar of the radio and television workers union must rank as one of the greatest accolades that can be accorded a man operating in the public space. The rather longish contribution of the author’s friend Akin Ajayi at pp171-178 is also a must read in this book.

By the author’s own admission, boredom and ominous intimations of a sudden and unprepared exit from office were to lead him into the legal profession. In the circumstance, it was to prove to be a most prescient move indeed. It also showed him as a man who is a cut above the rest. For he could have used the boredom differently – like acquiring several more paramours as some of his colleagues probably did!

His venture into the legal profession was to stand him in very good stead when the incidents he narrates in Chapter 8 (Legislature on Fire) unfolded like the Furies of Greek mythology. For anyone looking for where to begin to read this book from without starting at the beginning, this is the Chapter. The incidents narrated therein are of film show quality – and not just Nollywood. But there is also abundant humour.

Or how else were we to know that a challenge with one’s lumbar vertebrae could come very handy in a time of political tension? The schemes that got him out of harm’s way at critical moments were sometimes overseen and superintended by his childhood friend, Senator Gbenga Obadara, his creative accomplice – for want of a more apt description.

The author’s life-long friendship with Senator Obadara, despite the obvious inconvenience of the latter’s political differences with the powers that Badejo served during the Daniel administration, was also to be replicated in his association with Taiwo Adeoluwa, Secretary to the government that eventually cut short his career in the civil service.

Indeed, Adeoluwa’s input in this book speaks to the author’s uncommon large-heartedness and ability to make and keep friends across many of life’s artificial barriers and boundaries. His words in describing Demola’s role during the crisis in the House of Assembly would rank as perhaps one of the greatest tributes that can be paid to a career civil servant: “Neither side found fault with the quintessential civil servant and House Clerk”!

Surely, the author’s legal training helped him navigate the turbulent waters of the time, including his short sojourn at the ill-fated Lagos-Ogun Metropolitan Development Project. But the bigger lesson from his experience in the G15 vs. G11 drama at the Ogun House of Assembly is that partisanship is not likely to help you when your competence falls into doubt.

The author’s involvement in the management of the crisis in the House of Assembly was to be the trigger for his untimely exit from the civil service. In 2011, the new administration of Governor Ibikunle Amosun saw him as a Daniel loyalist; just like some elements at the inception of the Daniel administration saw him as an Osoba loyalist. And maybe before that, Chief Osoba may have also viewed him as a military apologist.

It must be a great tribute to the author’s professionalism and competence that each new government he served saw him as a loyalist of the last regime only for him to go on to provide superlative, unblemished stewardship to the new government. In this regard, I wish to believe that his premature exit from service was the loss of the Amosun administration.

How was Demola Badejo able to navigate the treacherous terrain of the service so nimbly and come out largely unblemished? I have no complete answer. But permit me to allude at this point to something General Charles de Gaulle, the great President of the French Republic once said.

De Gaulle had been confronted by a reporter who wanted to know where he stood in the raging East-West, Left-Right controversies of the Cold War era. De Gaulle calmly answered in his characteristic manner of referring to himself by name, “De Gaulle is not of the Left; De Gaulle is not of the Right. De Gaulle is above”!

Demola Badejo survived, I think, because he also stood above the petty civil service shenanigans that may have consumed less fortunate colleagues over the years and just focused on his work.

His exit from the civil service, rather than mark the end of the author’s active years was to propel him in another direction – business. Here his full Ijebu credentials came to the fore. And I should say that throughout the period he served as Permanent Secretary while I was Commissioner, Demola and I never had any disagreement over money. Quite remarkable you would say for any association involving an Ijebu man!

To his venture into business, Demola brought the same can-do spirit and enterprising verve that served him so well in the civil service. And he has made a roaring success of it!

It all started from the point of the registration of a business name. He had sent the name “Adeola Gbogbolomo” to the Corporate Affairs Commission as his preferred business name to reflect the identity of his darling wife and life-long business partner. But when the registration certificate came out, it carried instead the business name “Adeola Gbogbolowo”!

Was that the printer’s devil? Or, did the fellows at the CAC by some strange intuition know that they were dealing with an Ijebu man and simply affixed the more appropriate business title?! We may never know. But the name seems to have served the family business quite well.

The bearer of what should have been the original business name, his wife has been the pillar holding forth not just on the home front but also in business. Those seeking a clue to Demola’s multiple successes need not look farther than the home front. I rather love the way the author’s tributes to his parents-in-law dovetail into the celebration of his darling wife in Chs. 9 and 10.

One poignant incident narrated in the book is worth recalling here. The same vulcaniser who introduced him to the petrol retail business was to later nearly bankrupt the station through his underhand deals. What lesson are we to draw from this? My simple answer is drawn from the Scriptures: That God works in mysterious ways, His purposes to accomplish.

It is on the note of the inscrutable and transcendental power of Almighty God that I wish to conclude this review. It is also the note on which author concludes his memoirs. The final chapter (12) dwells on the author’s calling as a man of faith. For readers wishing to know the essential Demola Badejo and what makes him tick, that is the chapter to read.

Badejo, to paraphrase the great Nigerian editor, Mr. Ray Ekpu is a modest man who has a lot to be immodest about. Although descended from three generations of Jehovah’s Witnesses, he is however not a Witness by inheritance but by conviction and choice. This chapter helps the interested reader to get a grip on some of the popular misconceptions of the Witnesses’ creed.

The author advises that rather than “talk about your religion” let your life witness to others of the integrity of your professed faith. I say without hesitation that Demola’s life has witnessed fulsomely to Christ’s Great Commission as contained in Matthew 28:20. The rest of the chapter addresses Frequently Asked Questions about the Jehovah’s Witnesses that the reader will find useful and enlightening.

Is the book without any flaws or drawbacks? Far from it. But whatever the flaws are they are not likely to obviate its worth as an invaluable addition to any library. I doubt if “mom” as contained in p.10 is the language of formal communication. But maybe more modern editors will have their view on this.

There are a few typos, such as “lost” instead of “loss” at p.62; “UNICF” instead of “UNICEF” at p.69; “giving” instead of “given” at p.76; “hostel” instead of hotel at p.108; “extricate” instead of “explicate” at p.191; “adept” instead of “adapt” at p.198; and a few others. These, I am sure, will be corrected in the next edition, which should be coming out soon given the eager reception that the market is likely to give to this well written and easy-to-read book.

My last complaint about the book is of a personal nature. At p.xii, the author refers to Mr. Ibi Sofekun, former General Manager of the Ogun State Printing Corporation, which Demola also once headed, as his “friend and partner in matters relating to printing”. I really wonder how many people who know both men will agree that their partnership was only limited to printing!

I thank you all for listening.

Kayode Samuel

Abeokuta, 20/01/2022